Reading Sample

Reading sample

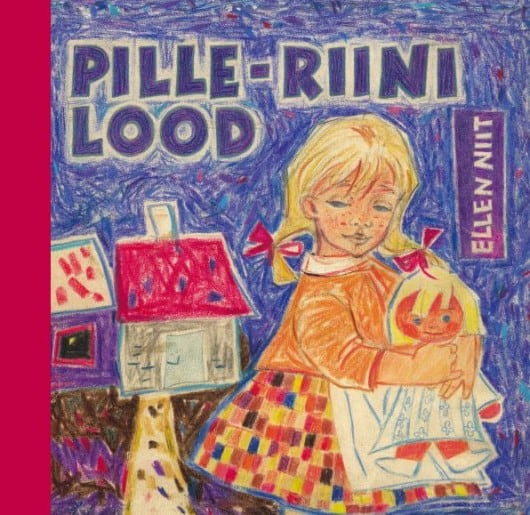

Pille-Riin and the Two Black-Eyed Bullfinches

Pille-Riin was sitting at the kitchen table with a big bowl of porridge in front of her. The porridge’s cheerful yellow butter-eye was watching the girl, and it even seemed to secretly smirk at her from time to time.

The chubby-cheeked boy on Pille-Riin’s milk glass was most definitely smiling at her, in any case. The boy’s name is Sass, and Pille-Riin usually liked him a lot. He liked Pille-Riin, too, because why else would he be staring at her with such a happy look on his face? Dad said that Glass-Sass looked so jolly and had chubby cheeks because he always drank the milk that Pille-Riin didn’t finish. That could certainly be true, because it wasn’t uncommon for Pille-Riin to not finish her milk. But today, Pille-Riin didn’t like Sass, nor did she like her porridge at all. She thought it was nasty and bad, even though that wasn’t fair, for how could porridge with such a cheerful eye be nasty and bad!

Still, Pille-Riin didn’t give Sass a single smile, much less the porridge. She was pouting and wouldn’t even look in their direction. Instead, she scowled and poked her finger through the hole in the oilcloth, making it bigger.

Pille-Riin’s mom called it a “tablecloth”, but her grandpa said “oilcloth”, and Pille-Riin called it an “oilcloth”, too, because she liked the sound of it better. She was glad that the oilcloth was laid over the table today, because tears were dripping from her eyes and onto the table. Sass stared at Pille-Riin in amazement, because he never cried. But what did he have to cry about, anyway? He didn’t have to eat porridge!

Still, crying wasn’t improving the girl’s mood at all, the heap of porridge wasn’t getting any smaller, and her dad didn’t call out from the other room: If you can’t finish it, then you may leave the table. Pille-Riin stopped crying and started scratching at the bowl’s pretty gold rim. Her dad said a long ray of sunshine had been caught in the factory, and was now put on the rims of children’s bowls to make them pretty and rich in vitamins. That was what Pille-Riin was picking at now.

However, it wouldn’t come off, and Pille-Riin was still in a bad mood.

There were two bullfinches on the bottom of Pille-Riin’s bowl. One of them was sitting, the other was flying, and both had red bellies and black eyes. Pille-Riin always smiled when she saw them. But right now, she couldn’t smile, because she couldn’t see the bullfinches.

Only the porridge was winking its yellow eye at Pille-Riin. This made Pille-Riin feel even worse, so she snapped at the porridge: “You’re bad and I can’t stand you!” Then, she took her spoon, stuck it into the bowl, and mixed the porridge up so that even the bullfinches underneath would feel bad.

The porridge no longer had an eye, and nor was it smiling anymore. This made Pille-Riin even more cross, so she said: “You’re dumb, porridge! It serves you right to be blind. I don’t want you; you’re nobody’s porridge at all.” Then, she started crying again and looked out the window.

The window was open and she could hear water trickling loudly outside. She reckoned spring was on its way. Pille-Riin cried quietly so her dad wouldn’t hear her, because Dad doesn’t tolerate crying. But spring had truly arrived. There was a big icicle hanging right outside the window. It dripped and sparkled: not just to cause trouble, but because of the thaw. Soft white clouds were piled up high in the sky, and the big, cheerful yellow eye of the sun flashed through them from time to time. The sight only reminded Pille-Riin of her mixed-up porridge, and she continued crying.

But suddenly—what do you know! Pille-Riin hurried to dried her eyes with her palms, and sniffled: outside, at the top of a birch tree, were two bullfinches. One was sitting, the other was flying, and both had red bellies and black eyes.

Pille-Riin was quite shocked. She eyed her bowl of porridge, and then the bullfinches outside again. Could it really be possible? The bullfinches on her bowl were the exact same.

Frail branches dangled from the birch tree. They swung gently in the breeze as the bullfinches flitted between them. But there was no birch tree on the bowl…

So, maybe they weren’t actually her bullfinches? Pille-Riin picked up her spoon and began rapidly emptying her bowl. The meltwater dripped and trickled outside, and every now and then, Pille-Riin would peek at the window with one eye.

All of a sudden, her porridge was finished. And there at the bottom of the bowl were Pille-Riin’s bullfinches! One was sitting, the other was flying, and both were staring at Pille-Riin with their black eyes. Pille-Riin cast a quick glance at the window. Lo and behold: the birch tree was empty! The birch tree was empty! The bullfinches weren’t there anymore.

Glass-Sass smiled happily at Pille-Riin, because the whole scene made him very glad.

Tracks

Pille-Riin and her grandfather reached the top of the steep slope. Down below was the dark, snow-speckled forest, and beyond it was the bog with power-line pylons striding across it.

“That’s the edge of the world,” Pille-Riin said. “This is where it all ends.”

“Is that so?” Grandpa chuckled. “Who told you such a crazy tale?”

“It’s not a crazy tale at all,” Pille-Riin said. “It’s the truth. Dad always says this is the edge of the world.” She stared far into the distance, beyond the forest and the bog, where the land and the sky met.

“But what about the forest, does that mean it’s past the edge?” Grandpa asked.

“Yes, it’s already past the edge,” Pille-Riin confirmed. “And the bog is on the other side, too.”

The yellowish sun stared at them from quite far above the outermost edge of the world. The snow on the hillside was pure and unbroken.

First of all, Pille-Riin wanted to show her grandfather the big pine tree, under which she had found three chanterelle mushrooms last summer. It was right there on the hilltop, so they set off towards it.

The pine tree was snowy and sleeping, and there was no sign of the mushrooms anymore. Even so, there was something else beneath it.

“Look, look!” Pille-Riin exclaimed. “Someone has been here!” She squatted down. The snow under the tree was full of tracks.

“Look—was there a dog walking here?” Pille-Riin asked her grandpa, pointing to paw prints that looked as if they’d been pressed into the snow with big pinecones.

“Yep, that’s a dappled dog,” Grandpa said.

“You can tell from the tracks that it’s dappled?” Pille-Riin asked in amazement.

“Of course!” Grandpa replied, chuckling.

“Is it dappled brown and white?” Pille-Riin asked.

“That’s what it looks like to me,” Grandpa said. “And it has a pointed tail that sticks straight up.”

“How do you know?” Pille-Riin asked.

“Well, if it’d had a droopy tail, then that would have left a track, too. But there are no tail tracks here,” Grandpa said.

He was right: there were no trail tracks to be seen. There were, however, a whole lot of bird tracks, which looked as if they’d been embroidered onto the snow.

“Look, a bird was here,” Pille-Riin said. “And it was right next to the dog. I wonder if they’re friends, since they were running around together?”

“Yes, I suppose they must be friends,” Grandpa reckoned.

“And check it out: there was even a kid here, too! One with bumpy boots!” Pille-Riin cheered. “Careful not to step on it.”

“Right you are: a kid, plain and simple,” Grandpa said. “Red boot tracks, if I’ve ever seen any.”

“Then it was a girl,” Pille-Riin said. “But the bird and the dog weren’t afraid of her, were they?”

“I suppose they weren’t,” Grandpa said. “I suppose all three of them were friends: the kid, the bird, and the dog.”

It was as still as could be on the hillside. Pille-Riin squatted and studied the tracks. Only the power lines crossing the woods buzzed softly.

“Are these tracks here because war will never, ever come again?” Pille-Riin asked.

“It sure is a sign that this is the millennium,” Grandpa said. “You see, they were looking out over the forest and the edge of the world here. No doubt they were listening to the power lines singing.”

“But do those lines cross over the edge of the world?” Pille-Riin asked.

“They sure do,” Grandpa said.

“And is that also a sign there’ll be no war?”

“It’s a sure-fire sign,” Grandpa replied.

They stood there on the edge of the world for a while longer, listening to the power lines sing.

Rawr

It wasn’t part of a dream at all, because when you opened your eyes, everything was there for real. You don’t see things like that when you’re dreaming, you can’t really touch things, and nor do they smell like anything.

But now, Pille-Riin was in bed, her nose was pressed against her big yellow teddy bear’s soft paw, and the paw smelled like honey. It was because all bears in stories love honey, and certainly also because Pille-Riin’s teddy bear was so yellow that it looked like he was doused in honey, even though he was fuzzy. But a little of his honey-scent came from the gingerbread that was in Santa Claus’s sack of presents, because that’s precisely where the teddy bear came from. Pille-Riin had named him Rawr, because a bear says “Rawr!” when you try to put him to bed. Dad laughed and said that Pille-Riin’s own name should be Pille-Rawr, because she grunts and groans over bedtime even more than a bear would. But that wouldn’t be quite right all the same, because Pille-Riin always closed her eyes in the end when nothing else worked—Rawr, on the other hand, never, ever closed his eyes. Pille-Riin had checked many a time, but she always found them open and glinting.

Today was Christmas Eve, and Santa had already come. Now, it was nighttime. But Pille-Riin wasn’t asleep yet, because there was still one white candle left lit and dripping wax on the Christmas tree. Mom had left it lit for Pille-Riin so the room wouldn’t be as dark as she slept, since Mom and Dad and Grandpa were all in the other room.

The candle burned and Pille-Riin was silent, thinking back on all that had happened that day. Rawr was staring at Pille-Riin with his ears pricked, even though Pille-Riin was as quiet as could be.

They had brought the Christmas tree home today. Grandpa fetched it early in the morning, set it outside, and two red-bellied bullfinches flew around it all day long. Pille-Riin reckoned they wanted to come inside with the tree. Yet when Pille-Riin went out with Dad to bring the tree in, the bullfinches flew away.

Mom came home very early and the two of them made gingerbread cookies together, which were now on the table next to the Christmas tree.

Mom cut out gingerbread flowers and stars while Pille-Riin made dogs, bunnies, and moons. She even gave the moons and the bunnies nuts for eyes: one for each. The moons got eyes so they could watch Pille-Riin and the Christmas tree, while the bunnies got them so they could run away from the dogs. Pille-Riin didn’t give the dogs eyes at first, but then, Mom said they would feel sad that way and wouldn’t be able to see their tails to wag them. So, Pille-Riin gave the dogs eyes, too. But she told each and every one: “Make sure you don’t peek at the bunnies!”

Then, evening came, it grew dark outside, and the scent of the Christmas tree seemed to grow even stronger inside. The whole house was filled with it. Pille-Riin started feeling a strange tightness in her chest, as if she was afraid of something. She supposed it was because Santa was coming.

Once the candles had been put on the tree and Mom was just beginning to light them, the doorbell rang. Pille-Riin thought it was Grandpa, because he had stepped out to fetch the newspaper a moment before. But when Pille-Riin opened the door, Santa Claus was standing there! Pille-Riin startled and sprinted into the other room, leaving the front door wide open. Santa let himself in, followed her, and asked: “Does Pille-Riin live here?”

Mom was the one who answered that Pille-Riin sure does, because Pille-Riin was hiding behind her mom’s back and couldn’t bring herself to speak.

Even so, Santa Claus smiled. He had a big, white beard and a red coat. The fringes of his coat were all beardy. But his boots were almost the same as the ones Grandpa had.

Mom pushed Pille-Riin closer to Santa, who asked her to recite a poem for her presents. Santa Claus cleared his throat with such a friendly noise that Pille-Riin didn’t feel as frightened anymore. She didn’t recite any poems, but told him a story about a hare and a hedgehog instead. Santa apparently liked the story, because he opened up his sack and all kinds of things started appearing. Pille-Riin got a ball and a big bag of candy and gingerbread cookies. Dad got a new pen and Mom got two books. Santa even left a present behind for Grandpa, even though he wasn’t there to recite any poems.

After that, Santa started tying up his sack. Suddenly, the sack went “Rawr!”. Everyone looked at one another in surprise. Santa Claus scolded the sack: “What do you think you’re doing, silly…” But the sack replied with yet another “Rawr!”.

At that very moment, Santa Claus let a yellow teddy bear out of the sack: he got out just for grumbling, which usually won’t get you anything in the world. Pille-Riin thought Santa would certainly put the teddy bear back into the sack, but he didn’t, and Pille-Riin got the bear as her very own to boot.

Now, Rawr was lying in Pille-Riin’s bed, and the girl thought she just saw him wink. She was probably just feeling sleepy. But at the same time, the candle atop the tree seemed tired as well, because the flame started sputtering and went out. Then, Rawr really did close his eyes. At least it seemed that way. She couldn’t tell for sure, because it was dark. Pressed against Pille-Riin’s cheek, Rawr’s soft paw still smelled like honey, and the candle wick still glowed red in the Christmas tree. And Pille-Riin felt just wonderful.

Translated by Adam Cullen