Indrek Koff

Indrek Koff (1975) is a writer, translator, and publisher, who graduated from the University of Tartu in French language and literature. He writes for both children and adults, translates French and Portuguese literature into Estonian, and runs a publishing house. Koff has written nine children’s books and several plays (in collaboration with Eva Koff). The author’s works are characterised by compact writing in broad strokes, occasional inner monologues, and alternating viewpoints.

Profile photo: Dmitri Kotjuh

Awards

2026A. H. Tammsaare Literary Award (

Don't Expect Anything)

2022Latvian Children's, Young Adults' and Parents' Jury, nominee (age 5+), (

Homeward)

Bologna Ragazzi Award, 100 amazing books (

Where'd the Kids Go?)

Tartu Prize for Children's Literature (Childhood Prize), nominee (

Where'd the Kids Go?)

2021Karl Eduard Sööt Children's Poetry Award (

Where'd the Kids Go?)Raisin of the Year Award (

Where'd the Kids Go?)

Good Children's Book (

Where'd the Kids Go?)Nominee of the Annual Children's Literature Award of the Cultural Endowment of Estonia (

Where'd the Kids Go?)

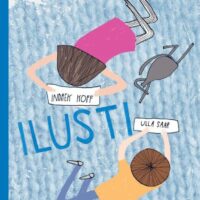

2016Good Children’s Book (

Ilusti)

2014Nominee of the Annual Children's Literature Award of the Cultural Endowment of Estonia (

Ten Little Butterflies)

Nominee of the Tartu Prize for Children’s Literature (Childhood Prize) (

Homeward)

Tower of Babel Honour Diploma for translation (Jean-Claude Mourlevat.

The Pull of the Ocean)

2013Nominee of the Annual Children's Literature Award of the Cultural Endowment of Estonia (

If I Were a Grandpa)

2011The Knee-High Book Competition, Honourable Mention (

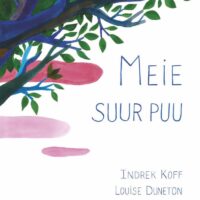

Our Big Tree)

Essay

While Indrek Koff has long been known as a translator and published a couple of poetry collections, Koff began writing for children just recently.

The first of his children’s books,

Meie suur puu (

Our Big Tree, 2012), supplies readers with a spectrum of topics, speaking about family and intergenerational ties. The latter are wonderfully conveyed with the image of a tree: the ancient native tree was once planted by the family’s distant ancestor, its roots extend deep into the earth of their home, children are able to climb and swing on its branches, and they can peer farther than their own noses into time and space.

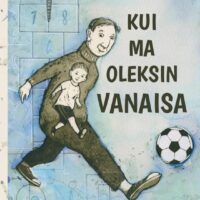

Kui ma oleksin vanaisa (

If I Were a Grandpa, 2013) similarly strings a bridge between the past and the future. The narrator is a child, but he fantasises about what he would do if he were a grandfather. A father of four children, the author allows himself to dream through the main character’s mouth about grandfatherhood, in which he will have an immense number of grandchildren. First of all, the grandfather would have very long legs so that all of his grandchildren could fit on his lap at once. Naturally, the grandfather and his grandchildren would climb to the top of an old maple tree and play spies in the yard day after day, would zip around on bicycles, and would eat pancakes that their grandmother makes. Together, the grandchildren and their grandfather would make up the world’s best group of playmates, no matter what they might undertake. Still, a more serious tone does enter Koff’s text, as is characteristic of the writer. Specifically, when the future grandfather must die one day, he will have a whole bunch of surprises already thought up for his grandchildren in order to lessen their sadness.

In his book

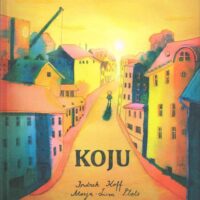

Koju (

Homeward, 2014), Koff manages to masterfully demonstrate how different a child’s perception of time might be from that of an adult. One day, five-year-old Madis has to walk home from the day care alone. The path that he practiced for a long time with his parents turns into a great adventure along familiar streets and backyards when the boy walks it alone. Madis encounters several grown-ups, with whom he has conversations and plays until it is finally already quite dark outside. Understandably, his mother and father are in quite a panic by that time. The suspense holds until the very last page – will everything still have a happy ending?

The collection of stories

Kirju koer (

Ten Little Butterflies, 2014) surprises readers with the breadth and depth of its topics, as well as with unexpected turns. Characters of all suits show up – for example, a fish with low self-esteem who is in a pickle, or an overview of brothers’ week that is given through the fights they have. We meet a cat who is angry at its owner and the leopard-model Tõnu, who also works part-time at the zoo as a professional leopard. All of these folk are very strange and simultaneously so familiar – Koff has managed to open up their characters and give them life by way of making them odd.

On the one hand, the author offers rather ordinary kinds of episodes and details; on the other, he gives his stories a philosophical depth outright magically. The collection is somewhat melancholic, but at the same time hopeful and optimistic. When a situation is just starting to seem too glum, the author bring in humour and notes of absurdity with unexpected trains of thought.

The book has a very wide target group: it reminds adults what it felt like to be a child, and at the same time gives children an inkling of how it is to be grown up. Koff is not the kind of children’s author who tries to win over his readers using cheap tricks. He is sincere towards children and does not underestimate them. Koff’s simply-worded stories do not underestimate the adult at the same time, either, offering food for thought about the nature of life. It’s definitely worth keeping an eye on the author.

Mari Niitra2.07.2015

Indrek Koff (1975) is a writer, translator, and publisher, who graduated from the University of Tartu in French language and literature. He writes for both children and adults, translates French and Portuguese literature into Estonian, and runs a publishing house. Koff has written nine children’s books and several plays (in collaboration with Eva Koff). The author’s works are characterised by compact writing in broad strokes, occasional inner monologues, and alternating viewpoints.

Indrek Koff (1975) is a writer, translator, and publisher, who graduated from the University of Tartu in French language and literature. He writes for both children and adults, translates French and Portuguese literature into Estonian, and runs a publishing house. Koff has written nine children’s books and several plays (in collaboration with Eva Koff). The author’s works are characterised by compact writing in broad strokes, occasional inner monologues, and alternating viewpoints.